November 1997

Curated by Neil Grayson

Review by Gerrit Henry

From zingmagazine, October 1998

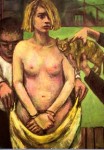

Now that the Age of Information has, via the ubiquitous media and the infernal Internet, handily swept away both the Age of Anxiety and the Age of Aquarius, is there, among cyber-saturated, fine-arts-starved, image-hungry younger American painters and sculptors, a new and growing kind of “return to the meaningful content”? For Alexandra Wiesenfeld, a visiting professor this year at the University of Iowa and proud author of a steady profusion of content-happy, often highly symbolic, new oils-on-canvas, the answer is a carefully qualified ‘Yes”. Content-happy? Wiesenfeld’s epic-scaled diptychs and triptychs have lots of tales to tell – The 7 by 13-foot Sea Triptych Turkish Adulteress, features a devastated nude woman on the verge of being stuffed into a bag with a cat and thrown into a river to either drown or be clawed to death. In Turkey, this has long been standard operating procedure, though we must know the story to completely get the picture.

And that affirmative to her role in a painterly return to meaning? “A lot of my work is from my imagination. But I always search for content, like the Turkish mistress, that will somehow get my ideas out” – poetic content, perhaps, in which to encapsulate the human experience, something like T.S. Eliot’s fabled “objective correlative”? “Sometimes I make up stories that I will base a whole series on – I’ve even done a kind of female ‘Twelve Stations of the Cross’, 14 paintings that I called The Madness of Queen M. The return to human content apparently need not mean a fixation on content: “If a painting is based only on content, it fails. It becomes an illustration.”

Wiesenfeld doesn’t make too much of it, but her father is Paul Wiesenfeld, an American realist very popular in the ’70s, who, family in tow, commuted back and forth from Europe to the States during the artist’s formative years. Says the 30-year-old painter, “Growing up in Germany, I always thought painting should look like Max Beckmann’s or Georg Baselitz’s.” In fact, early twentieth-century expressionist Beckmann ” is my all-time hero. I am half-German; my mother was German. I didn’t paint or make art when I was growing up – I think I was supposed to study philosophy. But Beckmann was a revelation – art should be ugly, it should make you uncomfortable.”

All of Wiesenfeld’s paintings, to varying degrees, utilize provocative, sometimes dreamily feminist subject matter to inspire discomfort, whether they be the overhead-looking-down, futuristic spectacle of Woman and Lawnmower, the outright absurdist comedy of the huge, hugely entangled Octopus Woman, or the sexy, anti-sexist poignancy of Schadenfreude, which lives up to its German title (‘taking delight in the misfortune of others”) as various and sundry, out-of-frame males take outsizedly evident advantage of a sad, prone nude.

If there is a growing school of distinctly post-modern, no-photo-realist figurationists, Wiesenfeld, a decided spearhead of the movement, aptly expresses her generation’s general, genuine distrust of the sort of sub-literary social commentary early-modernist Beckmann went in for to try to justify his aesthetically much deeper distortionist impulses. “The content is what gets me going. But the figurative element is also for structure, and once I start painting, the painting takes over.”

On the other hand, artists of Wiesenfeld’s sociocultural vintage have a distrust of pure formalism, doubting if that was possible even during the predominance of abstraction in America over the past 50 years. “If I don’t feel strongly about my content, I usually don’t get a good painting out of it.” Is Wiesenfeld daring to suggest that style and content – as they always have been until this century – might be co-equal concerns, instead of rivals, that abstraction and figuration still can be successfully synchronized in Western art? Again, the painter affirms a return to the figuratively rendered subjective over the abstractly rendered, so-called objective. “Human beings are so much more complicated than their shapes. For so long it’s been, ‘It’s not honest if you use content.’ But I tend to look at things as a metaphor for painting – the way our minds put thoughts together. It’s not a matter of traditional linearity, but it all overlaps and ties in.”

Paramount in the minds of younger American artists bucking computeristic techno-babble and videoistic visual lunacy is a renewed interest in human physicality as a legitimate subject matter for art, a concern that has manifested itself, from Durer to Velasquez to Rembrandt to Munch to Picasso – indeed, since the dawn of humanism in Western culture in the Renaissance – in the notion, most often embodied in self-portraiture, that the sheer materiality of the human form, and the face especially, is somehow spiritual, the body, artistically apprehended, being a plastic vehicle for the soul. It is only with the rise of European modernism in the 20th century that artists began to assume that the complexities of a corporeal being could best be represented by a decorporealized art, a brand of world-scale cultural gnosticism that contemporary representationalists like Alexandra Wiesenfeld doesn’t even bother to deplore. Instead she professes a profound, liberating aesthetic solipsism. “Every painting you do, no matter what, is a self-portrait.” Yes, this has probably always been the case in our culture – even, or especially, in the case of the dynamic duo that first brought “pure” abstraction to these shores in the ’50s, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. These bohemian titans invented the first, and perhaps the only means to present the human psyche abstractly, even objectively, in a kind of continuing all-over self-portraiture of the artist in the act of painting, herself, himself, and ultimately, itself. Perhaps, though, our immediate psychic forefathers never intended the thing to turn so pure as to encompass the complete “dematerialization of the art object,” as that maven of the conceptual, Lucy Lippard, so ponderously phrased it in the 1970s. Western art has always been “dematerial” in its promoting of the natural as the divine, the incarnational as the real, the mundane as the sacred, the latter in the mode of European still-life, the first in the landscape tradition, the second, again, in portraiture, this manifesting in that quintessentially Western art of the human being humanly – not animally, or vegetably, thus uncommonly, even celestially – perceived.

“All my figures tend to look like me,” says Wiesenfeld. “It’s personal. I have a few subjects that I keep coming back to. I see them through my own eyes. I’ve even been a voyeur, in earlier work. Now everything is more out on display for everyone to see. Either way, it’s existential.” Gee, but it’s good to hear that metaphysically human term used again – and used properly, to describe the eternal impetus of all art, and used literally, too, in the case of Alexandra Wiesenfeld’s daunting and undaunted, endearingly meaningful visions.